Death and traditional African funerals

Muslim death and funerals

Under Islamic tradition, deceased people should be buried as soon as possible. Cremation is prohibited but embalming is allowed under certain circumstances. The body is washed by close family members of the same sex as the person who has passed away, and then wrapped in sheets for burial. The funeral service is led by an Imam. The body is buried without a coffin and facing towards Mecca. The mourning period lasts for forty days and the community will feed the family for three days after the funeral.

Sarjo Koita, Mandinka, Gambia, on death and burial in the Muslim tradition:

“Religion will tell you that nobody can die before their time. If your time comes up, you go, and that is the fate we are taught and we know. So, still will have their traditional belief that somebody has died because of this and this but if you are religious you don’t think that way… If someone dies, depending on the time when someone dies, because as a Muslim, if somebody dies you have to bury the person as quickly as you can. A corpse should not be staying for that long. So, if a person dies, let’s say in the morning, depending on what time, and depending on his body condition. Because normally, we don’t take them to a mortuary. Unless they die from hospital, a bigger hospital, where there is mortuary. But, otherwise, if they die locally, you can’t keep the body for that long. Because of the decay. So, what you do, you try to announce the death. People will gather together. They’ll talk about the person. They’ll wash the body. Clean it…dress him up. Put him in a coffin. People will come. After ceremony, talk about his good. And the family…consoling them and so. Then bury the person. Everyone is buried.”

Sarjo Koita, Mandinka, Gambia, on death in Scotland:

“Well, in Scotland, here…to be quite honest, you know…we have few funerals here of our Gambian community who died. So, like, we have to do the same thing. Coz, normally when our people die here, unless it’s not affordable, the parents back home want the corpse back. You know, we transport the corpse back to the family. Even, at that, you have to do it through a funeral service guy. Who will take the body from the hospital? Depending on his religion. You know, whether he is a Muslim or a Christian. If you are a Muslim, then you arrange it with the Central Mosque of Glasgow. To be honest, I haven’t witnessed here, where a Gambian die and buried here. So, since I came here to Scotland, we had only two deaths of Gambian. And both of them, their body get flown back to Gambia.”

Serign Sanneh, Mandinka, Gambia, on Muslim burial:

“Burial is very simple. People are buried in white sheet and pretty much that’s it, so everything else is left behind… In the Muslim tradition in Gambia, it’s mainly, eh, a quick one and it’s scary, before it used to be scary and it’s something that people hardly really speak about and it’s always a quick thing when somebody dies, unfortunately, but then within a few hours they’re buried. If it’s at night, then they say “Okay, we leave the body and burial passing in the morning.””

Death and burial amongst the Nuer of South Sudan

Men are often buried beside their huts but also out in the wild if they die there. If they are buried by a stranger, that stranger will later demand a cow in payment. Women are buried under their husband’s house as they are seen as the property of the husband. Children do not attend burials.

Simon Koang, Nuer, South Sudan, on death and burial:

“If your father or your mother or young boys or lady die in the house, they put it behind the room, outside room, behind the room. Anybody die, they bury them there… Only the elders, the youngers they don’t go to do that… No, because last time we don’t have clothes. No clothes. But now we use the black clothes, when there is…somebody died. Because, last time when somebody die, we don’t have clothes. But, all the elders, all the women…they will tie their stomachs with rope. They will tie their stomachs with rope. And not eat food for five day. All the brothers, all the fathers, all the mother. The big elders of the family. They will tie their stomach with rope.”

Younis Odum, Ghana, on death:

“Ehm, it’s feared in a way…no-one wants anyone to die so, for example, if someone dies in someone’s family they would be like “Oh, come back, come back.” If the person hadn’t totally gone and they rose up again they would flee in an instant.”

Gloria Oju Onyekwere, Kaduna State, Nigeria, on death:

“Yeah, yeah, there are so many ways, depending on your religion. You’ve got the Pagans, the Christians, the Muslims, so whatever religion you believe in, like, if somebody pass on, you can, if somebody a Christian, mostly they will recommend that you wear white attire on the person, and if you a Pagan you wear black attire on the person.”

Ali Abubakar, Zanzibar, on Muslim burial:

“Funerals are conducted in your local mosque. You have three nights of mourning. Women will be gathered (like a wake). Say it was a death in my family, then you will have a lot of women who will come from nearby and literally spend three days in the home to mourn together and to help the mother or whoever in the home… In a mosque there is one coffin, and that’s the coffin that is used for everybody, in such a way that the person is in coffin and is carried by people. You walk to the graveyard, and then bury in the graveyard, and then the coffin goes back to the Mosque and gets cleaned ready for the next funeral.”

Ali Abubakar left Zanzibar in the early 1960s and converted to Christianity:

“My change to Christianity wasn’t a chosen one, it wasn’t, what’s the word, it happened. I was on my own and it happened. I didn’t discuss this with anybody and I had to start picking the right person to ask and I grew that way and there’s no…any regret. Was a long time ago thinking that how could I possibly become a Christian, coming from my family you know, but that change took place.”

Boris Zamba, Cameroon, on death:

“But for the funerals, it depends who you were when you were living. If you were somebody, especially a man, that died without any kids, then they are going to bury you in a kind of normal way. So, it’s just people come, they make the traditional things, they bury you. They don’t allow people to mourn too much. If you are somebody that has a heritage, heritage is kids, then there is going to be a big ceremony for the funerals. The big part of it is four to five hours. [When asked if this happens in Glasgow], no chance, no chance.”

Pa Ebou Ngum, Wollof, Gambia, on Muslim burial:

“Back home, we have a place where normally they do their special bath before burial. So, from the mortuary they took them there, he or she. Woman is bathed by woman, if it’s a man is bathed by a man. After the bath, is a special way of dressing them and then to the, the burial, the grave.”

Rohay Conteh, Mandinka, Gambia, on Muslim funerals:

“Mainly, because Gambia’s got, eh, Muslims and Christians and other…there is some other people, as well. Like, different from Muslims and Christians. Yeah, who practise other things. But they’re minorities. But, yeah, Christians do their normal burial…coffin, get dressed and stuff like that. And then also, you have the Muslims as well. Just get burial, the same way as Muslim way.”

Rohay Conteh, Mandinka, Gambia, on death in Glasgow:

“Yes, most people send their people back to Africa. Even though it’s very expensive. But they try. It takes a long time sometimes. It depends sometimes on the family, financially. Some families will take their dead body quicker than others. It will take a while. And for some…I think they have to be buried here. They don’t have any finance or any family.”

Guy Ngansi Deyap, Bamiléké,

Cameroon, on death and financial contributions towards the funeral from Glasgow:

"Ceremony of death, we spend millions when somebody passed away. I’m trying, I say to myself, when somebody’s ill like now, my mother’s in hospital for one month, nobody even gave me a call to see how she’s doing. Yeah, but if my mother passed away now, they will say “Oh, you going to be coming here to give me money, for what?” (laughs) That is what I’m asking, “For what? What will the money be used for, eh?” No, it will not make my mother come back. So, the African countries they celebrate the dead.”

Sean Thomas, Lagos, Nigeria, on funerals in Lagos:

“Well, I know, in Africa, where I come from. Uhm, cremation was never a big thing. It was always, you know, dust to dust. It was what was believed. It, uhm, always starts from a wake keeping. There’s always a wake. Which is normally two days before the internment. That’s the burial. And, umh, if this person is an older individual, it’s often celebrated. Older individual meaning anyone seventy, eighty. That has lived a long and fruitful life. Usually, it’s more like there is a party after the body has been laid to rest. There is like a celebration of life. We’ll put it that way. So, it’s more lively, whereby people come together and they celebrate the life of this person that is gone. But, if it’s somebody younger and it’s a more tragic situation. It’s often very quiet. And you know…the parents are never allowed to go to a child’s burial in Africa. If, you know…it’s something that’s not really accepted widely, you know. If a child dies at a young age, in Africa, they don’t expect the parents to go and bury the child. It’s not something that any parent would wish for. I am guessing it’s partly the same in this parts of Scotland as well.”

Nelson Sule, Benin City, Nigeria, on funerals in Benin City:

“Like in Benin, Benin City, what I know about it…I’ll use my grandfather as an example. Ok, I’ll start with…normally when someone dies, we don’t…we celebrate the person’s life. It’s like a celebration. And, umh, even though you wear black. You can wear black during the day but during the burial proper, you don’t normally wear black. You can wear black during the day. But, during the celebrations proper, you change from black to the African, eh, traditional wear… And ehm, like for the man…if it’s his wife that died, he can’t attend. Ehm, because, if you’re older than the person that dies, you cannot attend that burial. Eh, the burial’s usually done by the people younger… Then eh, like eh…or my granddad, when he died the celebration lasted for seven days. This is to symbolise his status in the community. The first day celebration was full. During the seven days there was lots of feasting going on, eh, lots of drinking going on. And, uhm, basically that’s it…”

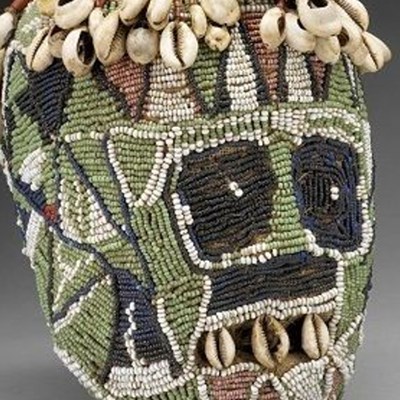

Jean Albert Nietcho, Bamiléké, Cameroon, on how he hopes to have his skull preserved in Cameroon and become a divinity as an example to his children:

“Yeah, I believe in reincarnation. That’s the base of, actually, my tradition. Because we believe that they come and speak to us. They look after us. They advise us. And you have to be in connection with them. If you are disconnected with them, you may not hear them. So, you have to believe in it, so you have to believe…you have to believe in it. That’s why I believe… I also believe that…because what we did, where I came from, Bamiléké, in Cameroon, when you pass away, they bury you. When you stay maybe, for two years. When it’s only, the, the skeleton. They will come and get the skull…they will come and get the skull. They will put it in the special house. Ancestor, they call it ‘ancestor house’. They will put it by generation. But as I am talking, I can go back with my kid. But you will not see the skull. They will put it somewhere you cannot see the skull. They will put it somewhere you cannot see. Oh, how do you call it again? They will put a container, a vase, over, over, over it. With water, with water only. And then you go there and give the food as well. When we go there, we will go and feed them. Sometimes we just, we just feed them. It’s a special food. Most of the thing that we do is the eyes bean (black eyed bean) and maybe the good meat, mix up. There’s a special way of cooking that. It’s not boiling. We burn it, like in the fire. We put it in the fire. We put it in the fire and they will have these insect that will come and eat it. Just like it’s the ancestor… And to be…it’s not everybody that will take the head off. The skull. It’s not everyone…so you have to live by example. If you are someone in your living time, who is not living by example. We will not take that out. So, to be a divinity. So, if you are not doing that. That will be a shame for your family. So, you have to make sure that when you pass away, you live by example. So…I do believe that…that’s why I’m very, very careful how I interact with people. What I do with people. Because I want to be a divinity. I want to be an example for my kid when I leave this world.”

Twimukye Macline Mushake, Bakiga, Uganda, on death among the Bakiga:

“I think death from, uhm, a community level, I know that even from as long as I was a child, there used to be funeral co-operatives. So, each household is expected to contribute a certain amount of money…not much…towards a funeral budget. And when someone dies the community gets together. They buy the coffin. The people come and dig the grave and buy the food or collect food from the community. Because, for us, mourning is four days. Especially a key member of the household. Children, yeah, they could be ignored, but, for the head of family or an adult, there is four days mourning as a cultural practice. And I think I’ve found that useful. In the sense that, you don’t expect going through grief, to then go through the nitty gritty of arranging all that. Other members of the community do. And that is one valuable practice that, I think, we still have, even today, in the village where I came from.”

Twimukye Macline Mushake, Bakiga, Uganda, on death in Glasgow:

“In Glasgow, we’ve got a few African people and I’ve seen…despite the fact that we come from different African countries. People have gathered together. Have contributed some money. Umh, to buy a grave. The community have contributed money to take the body home… I’ve already made my decision. If I die in Scotland. I don’t mind being cremated. Which is something that would be contrary to my culture.”

Mourning colours in West Africa

In West Africa, all the colours have similar meanings to those we are familiar with in Glasgow. The only exception is the colour red, which can also symbolise grief and mourning.

Lydie Bere Flere Dossa, Akan, Ivory Coast, on funerals amongst the Akan:

“You wear dark and red when you go to funerals. Dark and red or white and black. Or white or sometime all black. When it was young couple and one of them is departed. You wear black, because it’s very painful. Eh, but normally is white and black or red and black. Or white only when they are elders…you wear white only because the person has live his life. So, it need to be white.”

Chief Josephine Oboh-Macleod, the Esan, Nigeria:

“Eh, In Scotland I think some of them do get buried here, em, I don’t know how many will allow to be cremated because a lot of our religion doesn’t allow for cremation... I don’t see any reason why someone should not be cremated because even our oral history that was passed down, there had not been anything that had been passed down that said don’t cremate… The majority of us will have the burial but still, I believe that most of us will also send messages back home to let them know that the person is dead and whatever ceremony was to be done they will do back home and if they don’t, then it is not officially recorded. You cannot have a person die here and if they’re having contact with their roots and not tell them at home officially.”