Naming Ceremonies

Hausa

The Hausa are the largest ethnic group in West Africa. They are mostly located in north-western Nigeria and in neighbouring south Niger. Music and art play a big role in their everyday life and the Hausa are well known for their craftsmanship and crafts, which are sold throughout West Africa.

The wife is bathed every day during pregnancy and frequently after she has given birth. Guests are sent invitations to the naming ceremony on the sixth day after the birth. The father buys kola nuts (a West African nut used for its stimulant properties) to offer to the visitors. Food is also prepared and offered to the guests to mark the birth of the child. The Imam goes to the house and the women greet him whilst the men wait outside. He slaughters an animal provided by the father of the child. Everyone prays to Mohammed in both Arabic and Hausa. The Imam is then given gifts by the father.

Names are chosen from the Koran (or Qur'an) by the father, without consultation with the mother. Boys are named after prophets; girls names reflect historical figures, such as Amina and Aishatu.

Mandinka

The Mandinka live in a number of West African countries. The largest number are in the Gambia and make up 40 per cent of the population. They are descendants of the people of the Mali Empire, which stretched over most of West Africa and had one of the richest kings in history.

The process of pregnancy and childbirth is shrouded in mystery amongst the Mandinka. It is believed, for example, that talking about pregnancy and the future of the baby may bring bad luck and even endanger the life of the child. Once the baby is born many rituals are performed and traditions observed in order to protect its life. An example of this being that the mother is compelled to stay inside, with a fire to accompany her, for the first week after the birth.

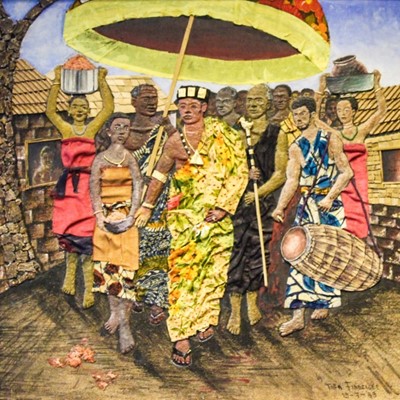

After one week, the naming ceremony takes place. The child is usually named after the relatives and friends on the father’s side of the family. The names are typically Africanised Arab names. The father invariably arranges the ceremony, which normally takes place in the morning. An elder will either shave the baby’s head or cut a lock of hair from the child whilst saying a silent prayer. He then whispers the chosen name into the baby’s ear. It is then spoken out loud. While this is going on, a chicken or goat is slaughtered. The lock of hair is then buried. Kola nuts (a stimulant indigenous to West Africa) and cake and other celebratory food is given out to guests. Guest in turn bring gifts for the baby. A big meal is then prepared, and celebrations are undertaken, complete with drumming and dancing.

Serign Sanneh, Mandinka, Gambia, on the naming ceremony:

“After seven days when a child is born, you have a naming ceremony, you have a ram, a sheep, basically a grand ceremony… “It’s an all-day party of food and dance, and because we, it’s a Muslim community we don’t drink but we have a lot of food and, and dancing and sometimes even masquerades. We have a traditional masquerade from the Mandinkas, called Kankurang, that looks like it’s an all red masquerade. The masquerade is usually red because they peel the back off a tree and that it is a red colour so that masquerade is like…. does dance and they go about with machetes and scare people off. It’s good, but in general it’s pretty much like that.”

Serign Sanneh, Mandinka, Gambia, on maintaining the naming ceremony traditions in Glasgow:

“Most people here do not like the kola nuts, like people my age and slightly older, it’s people like mums and dads that like the kola nuts… Nowadays the naming ceremonies here is like a big party, yeah, a big party, so basically it’s like an open-air concert for everyone.”

Yoruba, Nigeria

The Yoruba are one of the three largest ethnic groups in Nigeria. They have for many centuries been among the most skilled and productive craftsmen of the continent of Africa. They have worked at occupations including blacksmithing, weaving, leatherworking, glassmaking, and ivory and wood carving.

The Yoruba take the naming of a child extremely seriously, as it is believed that the name will have an influence on the fate of the child. The naming ceremony is traditionally carried out on the ninth day for a boy, and the eighth day after birth for a girl. The ceremony usually takes place early in the morning, with close and extended family and well-wishers present. The spirits of the ancestors are invoked for the ceremony. Native gin and kola nuts (a native nut that is used as a stimulant) are used in order to gain the blessings of the ancestors. Salt and honey are present to represent the sweetness and bitterness of this life. Bitter kola is used to represent long life. Alligator pepper (a type of ginger native to North Africa, with a hot spicy taste, used in both food and in ceremonies) symbolises the birth of many children. Everyone presents money in a bowl of water and then carries the baby and gives them a name. The names are then chosen by the ones that are used most for the child over the first few months of its life.

The child is given at least three names in order to guide them on the path of life. These may be:

- Amutorunwa name (name brought from heaven). This name is given to children born under the same circumstances. Most notably with twins. The first-born twin will always be called Taiwo (has the first taste of the world) and the second born will always be Kehende (he who lags behind).

- The ‘Orile’ name is indicative of the child’s kinship group. Names can also be given according to parent’s preferred deities, and sometimes the profession of the parent.

- A child born after the death of grandparents is called Babatunde or Tunde (the father has returned), or Yevande, Yetunde, Iydbode and Yeside (the mother has returned). If an elderly person names a child, then they can use that name for the rest of their lives even if no-one else does. There are many other categories of name.

Lydie Bere Flere Dossa, Akan, Ivory Coast, on birth in the Ivory Coast:

“Yeah, the birth, is in, two kind of birth, one you are a first mum, is your first child. Like, you are an orphan with your first child. You always gonna find somebody around you who can guide you. She will come and help you because you don’t know anything about child. She will help you to show you how to clean the child, how to give him his bath. What to do when the child is crying. The way to feed him. The way to change him. All of these ones she’s gonna give you the basic advice. And she gonna come, from time to time, to check on you, to check on the child. But, if you are not an orphan and you have a family….your mother….and if your mother come do it, she will do it. She will come and stay in your house for some time. Sometimes she can stay a year. Sometimes she can stay six-month, three months. And she’s gonna be the one to bath the child to even bath you as well, to give you some massage, cook for you and your husband…if you are married thing like this…So, she gonna show you all the step with that.”

Wollof

The Wollof naming ceremony is strongly influenced by Islamic teachings. It takes place on the seventh day after birth. The parents or grandparents choose the name. The baby is brought to the ceremony in a white cloth and the call to prayer is whispered into its ear whilst its head is shaved. Kola nuts are broken and a chicken or a sheep is slaughtered. Griots (story tellers) then announces the name and feasting commences.

Pa Ebou Ngum, Wollof, Gambia, on naming ceremonies:

“That’s one of our rituals that you have to….in the religion side. There are two aspects, you have the religion side and the cultural side. Like, the religion side, you have to give the baby name and recite verses for it and then the cultural side, we have the cousins. That come in for you and singing you the words of praise, you know, reminding you or naming your great grandparents, you know. It is a big occasion whereby, you know, you tend to dish out money to them. So, a sign of happiness and appreciation. That’s how we normally do our christening and wedding ceremonies… The only difference is like, normally we slaughter a sheep. So, that’s the difference, but what happen is like, normally, it’s communication, as soon as the baby is named a sheep is slaughtered back home.”

Younis Odum, Ghana, on the naming ceremony in her village:

“Well I don’t know much about all of Africa, but I know in Ghana when a child is named, well from my culture, they normally name the child within seven days and sometimes they do an outdoor where they bring the child outside for the first time and then they gather friends and family and then they give the child a name and then they do a dedication, if it’s a Christian family… “I’ve noticed that sometimes they can merge and do the naming and the dedication together, they just wait and do it all at Church.”

Younis Odum, Ghana, on traditions carried on in Glasgow, including the naming ceremony:

“I mean some things are kind of hard to pass up on, like your clothing, you can’t really pass up on that, and we, we've modernised it so like a fresh new look on that. Like the whole naming thing is still maintained here. Piercing a child’s ear when they a little girl still happens, the circumcision I know that still happens for boys. The whole ‘knocking thing’ my brother had to do that. So, most of those things are still in place here”.

The Nuer, South Sudan, and sacrificing cattle at life event ceremonies

Like many pastoralists the Nuer of South Sudan place a huge emphasis on the importance of cattle to the point that their society revolves round them. They are sacrificed during important ceremonies.

Simon Koang, Nuer, South Sudan, on the naming ceremony in South Sudan:

“The father will bring a cow, or a goat and he’ll kill it. All the people will make a party. After 42 days the baby his mother will come out of the room. The baby will stay in the room there’s no going out of the house until 42 days… From that day they will give a name for the baby. It will stay for 42 days, no name. They will give a name for the baby and they will have a party… “We have Christian cultures and traditional cultures.”

Simon Koang’s children were all born abroad, and he is one of only a couple of people in Glasgow from South Sudan:

“Yeah, my children…Two was born in Khartoum, and one - three was born in Kartoum, one was born in Cairo and one was born in Israel.”

Ofomu Clark, Edo State, on the naming ceremony in Glasgow:

“Yes, we do, but I, as a Christian, never did that, but we do… I did a child dedication in Church where I invited my friends and family and they came to do a thanksgiving session where they chose names. After that we have the party at home.”

Ofomu Clark, Edo State, Nigeria, on what traditions she is keeping in Glasgow:

“I still prepare traditional foods, I still wear my traditional attires… I’m trying to get my sons to know the traditional way and they love traditional food as well.”

Fulani Naming Ceremony

The Fulani naming ceremony is carried out under the dictates of Islamic law. It takes place after seven days, like many other West African naming ceremonies. If the child is to be named after someone then they play a special role in the ceremony.

Kaddi Jatu Jobe, Mandinka, Gambia, on the Fula naming ceremony that her baby had in the UK:

“Yeah, different, different tribes do it differently, but because my husband he’s not, he’s from a different tribe, he’s not Wollof or Mandinka, he’s Fula, so when I had my daughter, we had to do like the Fula tradition… My Mum’s tradition from the Mandinka is that when you have a baby at the naming ceremony the Mum would come and sit down, but with the Fula tradition the Mum stays inside, and the sister-in-law brings out the baby. So, when I had my daughter, my sister-in-law brought my daughter out for the naming ceremony, it was really nice, but the food and the other dishes are still the same… So, when the seventh day of the baby’s birth, we do have the Muslim ceremony. So, that only takes like a minute or so…so, what they do, they put the Adhan in the baby’s ear. That’s the call of prayer, in both ears. And, that’s it, but the rest of it is all traditional. So, we got the traditional…like these kind of wraps that we’ve got…I can show you. That’s what you get and wrap the baby in there. It has to be handmade. So, it’s handmade from Africa and sent out to us here. So, that’s what we use. And we have….so you keep it and then use it for all the babies… After the ceremony what we do. Is like so, because I couldn’t come out. That’s the tradition. So, my sister in law brought the baby out. So, after the ceremony they take…. they brought the baby back to the bedroom. So, what they do….they go like, oh, so in my language it means….I’ll just translate it for you. So, it means we’re selling the baby. And then you try to hold….they take it away. Are we selling the baby? (laughs) there’s a baby for sale. Then, when you try to reach the baby, they will take it back. They did it for. I think about 3 times and obviously then they give you the baby… So, when they’re doing the christening, we have a tradition…what you do….you put like a lot of salt in the water. So, like they tend to say ok, the more salt you put in the water. The more, like, kind of, liked, blessed or popular the baby will be in whatever they intend to do in their later life.”

Kaddi Jatu Jobe, Mandinka, Gambia, talking about post-natal care in Glasgow:

“They do yeah…so, I had my mum here. So, she tells me what date when you were pregnant. And I have other relatives….my aunties, my elder cousins as well as my sister in law as well. So, they are telling me….oh, this is what you do, this is how you do it and that kind of thing. And when I had the baby as well….my sisters in law they came. One came from America, the other came from Germany. And I had my mum as well from Reading. So, they were all…So they were all helping around. So, yeah, it was a house full of helpers. It was great, yeah.”

Gloria Oju Onyekwere, Kaduna State, Nigeria, on naming ceremonies in Glasgow:

“Yeah, I’m a mum of three. I’ve got two girls and one boy. I’m a Christian, like I’ve said earlier on. I practice the biblical way, which is naming ceremony on the seventh day. So, all my kids are named on the seven day. I get the pastor to the house. They pray and they declare…and they name the child and they say the meaning of the name… Most Nigerians were kind….I think every little thing were kind of…we are very entertaining…with foods, drinks and obviously our dance. So, after the naming, obviously, I present food to them and they pray over the food. And then others who have come to rejoice with me have something to eat and drink. And music comes on. Because those who know me know I love music and I love dancing. So, I can’t do anything without that taking place. Eh, it depends on what ceremony. If I am doing my naming ceremony, I’ll just do the basic food. Which is jollof rice, plantain…. then, the snacks which is our Nigerian meat pie, then puff puff. Then get the Nigerian malt, then obviously mix and match with the coke and Fanta.”

Alix Joseph Offorojamu, Nigeria, on the naming ceremony where he comes from:

“Yeah, if you are doing like naming ceremony you just gather the community together and everybody is playing music, happy, drinking, that’s how we do it.”

Alix Joseph Offorojamu, Nigeria, on the naming ceremony in Glasgow:

“Yeah, we are free to practice it, we don’t have any disrespect from the Scotland Government if we do anything like that. We do it here as well if we can gather the African people together.”

Chief Gift Kofi Amu Logotse, Ewe, Ghana, on naming ceremonies in general in West Africa and the belief in reincarnation:

“One thing we all have in common is it doesn’t matter what tribe you’re from if you’re born by the seventh day, you have a name you know, and not just any naming name, your first name that anybody will call and welcome you with is day you were born. If you’re born on Friday like me, you will be called Kofi and you can’t get away from that. I am no relation to Kofi Annan, the only thing we have in common is we are both born on a Friday, you know, and that’s it and then somebody else will look at you the way they have seven days like me and maybe they say ‘you’re behave like your Grandad look at you, you crying like him’ and the people who can do that are the older people, you know, so that’s why it’s always good when the child is born for an old, the oldest woman in the family or the oldest man in the family have a look at the child and they straight away can tell you who it is that came back, see what I mean?…and they will name and do things to celebrate and welcome that person back so what they’ve lost, they welcoming back from another way. So that is the concept behind which is come, it is comforting in a way.”

Nelson Sule, Benin, Nigeria, on naming ceremony in Benin City:

“From what I know, basically when a child is born, after seven days the child is named. On the eighth day, you will have a kind of celebration where the child is given a name and this celebration in my own family, each family has different ways of doing it. In my family we always give the Grandparents the honour of naming the child, that first child, we always give the Grandparents the honour of doing that. For my own child, my Dad was given the honour of naming my first child.”

Nelson Sule, Benin, Nigeria, on early circumcision and naming ceremony in Glasgow:

“Yes, like the circumcision, when I have, I’ve got two boys. When I have my two boys I had them circumcised within seven days in line with our tradition back home when we also did the naming ceremony as well for both of them, where we had the, the, we improvised where we could and some of the stuff we couldn’t get that signifies that is used to signify certain stuff for doing the ceremony.”

Salt and sugar in West African naming ceremonies

It is common in West African naming ceremonies for children to be given a taste of salt and sugar amongst various other things for different reasons depending on the individual tradition. This can represent various aspects of life but commonly it is associated with giving the child a taste of both the sweetness and the bitterness of life.

Birth – Day Names

Even before parents select a western or religious name for their child, the baby already has a name. Among some Ghanaian ethnic groups like the Akan, Ga, Ewe and Nzema, a name is automatically assigned based on the day the child is born, though the name may not necessarily appear on official documents:

Monday - Kojo (male), Adwoa (female)

Tuesday - Kwabena (male), Abena (female)

Wednesday - Kwaku (male), Ekua (female)

Thursday - Yaw (male), Yaa (female)

Friday - Kofi (male), Efua (female)

Saturday - Kwame (male), Ama (female)

Sunday - Akwesi (male), Akosua, (female)

These day names can vary slightly depending on the ethnic group.

Aya Rashid, Nigeria, on the birth and naming traditions in his culture:

“Most of the children are born in wedlock and for those that are born out of wedlock, they are treated the same way… When a child is born it is like a new whole world is just begin. Enemies put aside their differences, people put aside their beliefs, and work together to bring a new life into the world… People believe that on the seventh or eighth day of a child’s birth they have to be celebrated. They make the child taste honey, salt, water and sugar-cane.”

Sean Thomas, Lagos, Nigeria:

“We have um, the days the child is born sometimes we name the children according to the days they are born. Traditionally in Africa we have a naming ceremony seven days after the child is born, so if you were born on a Wednesday you would be named after Wednesday. There is a huge ceremony where family, friends, everybody would be invited to you know, name this child, and in Africa everybody has a name for the child - so your Uncle could come and say I want to call you Jack and your other Auntie can decide to call you Jill, but everybody has a name that they give the child, but the ‘name’ is the one that your parents have give you.”

Esan naming ceremony

The ceremony is held on the third month after the birth. The baby is often given a name with meaning pertaining to a significant event which was happening at the time of its birth; It may also be named after a person whom it is believed has come back through a process of reincarnation as the child. Ridiculous names are put forward and rejected at the ceremony.

Chief Josephine, Esan people, Nigeria:

“When it come to the time to name the child, normally the oldest, might be the father to the actual father of the child, because through Esan land they will throw the child up and they will throw the child up to about seven times very high up and catch them and then he’ll say “welcome to this world,” and we are all welcoming to this world and everybody now will start giving the names and the final person will give the honorary to the father or the father has given that honour to his father or one of the elders of the community, who will go up and say, “my name is this and the name I give this child is this.”

Guy Ngansi Deyap, Bamiléké, Cameroon, on why he loves his African name:

“Ngansi, I love a lot because Ngansi in my culture, my tradition, my mother and father dialect, because my mother and father are from the same village, it means that - got roots… You see, the roots of the tree, that’s why I got the meaning”.

Chief Josephine, Esan people, Nigeria, on naming ceremony in the UK and Glasgow:

"What we did was that we had the western naming ceremony at St Paul’s Church for my twins and then we also organised the African naming ceremony separately so where the African names were given, but we ensured the African names came first. Luckily for me at that time I was actually going back to Nigeria, so we had the African naming ceremony in Nigeria but then wrote to have the Scottish one here in Scotland at St Paul’s church who have good traditional naming ceremony which is African. When we had the African one we had a reverend I think from the Church of Scotland to the African naming ceremony to also give prayers to the children during the African ceremony with all the elders of the village, but if you cannot afford to do that what most Africans will do is to call the most senior persons here of their community and then give the traditional name to their children and go to church and recognise it also in the church… I think, Africa, one thing that we have which some people don’t appreciate even for an African brought up Esan, is that we are very rich in culture, we are very rich in humanity and we have a lot of festivals that bring happiness to the life of the community and, as you just said, one of them is birth. We used to believe and still believe that a child is a gift from God, given to you that you can’t buy with money.”

Mariarose Ngosi, Lilongwe, Malawi, on birth in Malawi and advice given:

“It was something that was special and only the ones who have gone through it and the older ones who were allowed to talk about it.”

Mariarose Ngosi, Lilongwe, Malawi, on the difference between gifts brought for the baby in Malawi and in Glasgow:

“No, we don’t have naming ceremony, no, but we do have…But we so have like, eh…. people coming to see the baby. So, they’ll bring things like…I remember I was talking to my friend here. I was telling my friend here. When you go and see the baby you bring money and clothes and what…but in Africa it’s completely different. Eh, you can bring even live chicken to come and see the baby (laughs). So, I used to laugh with my friend. So, my friend used to laugh with me to say-What will the baby do with the live chicken?! Yeah, it’s a cultural thing. So, you do bring gifts, but, eh, there is no naming ceremony in Malawi… Yes, we do have a Catholic christening.”

Next page: African Rites of Passage